Issue 15: Intersectionality

Printable PDF Version

PlainText Version

Effectively responding to gender-based violence (GBV) requires addressing the multi-dimensional and complex circumstances of identity and oppression surrounding every survivor and every individual who uses violence.

But what does this really mean?

Intersectionality is made up of 3 basic building blocks: social identities, systems of oppression, and the ways in which they intersect.

- Social identities are based on the groups or communities a person belongs to. These groups give people a sense of who they are. For example, social class, race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation are all social identities. A person is usually a member of many different groups or communities at once; in this way, social identities are multi-dimensional. An individual’s social location is defined by all the identities or groups to which they belong.

- Systems of oppression refer to larger forces and structures operating in society that create inequalities and reinforce exclusion. These systems are built around societal norms, and are constructed by the dominant group(s) in society. They are maintained through language (e.g. “That’s so gay”), social interactions (e.g. “catcalling” women), institutions (e.g. when school curriculum does not acknowledge residential schools), and laws and policies (e.g. immigration policies that make it difficult for new Canadians to access health services). Systems of oppression include racism, colonialism, heterosexism, class stratification, gender inequality, and ableism.

- Social identities and systems of oppression do not exist in isolation. Instead, they can be thought of as intersecting or interacting. In other words, individuals’ experiences are shaped by the ways in which their social identities intersect with each other and with interacting systems of oppression. For instance, a person can be both black, a woman, and elderly. This means she may face racism, sexism, and ageism as she navigates everyday life, including experiences of violence.

AN INTERSECTIONAL MODEL OF TRAUMA FOR SERVICE PROVIDERS

Gender-based violence (GBV) impacts the mental health of women and girls, with gender playing a significant role in the types of traumas women are likely to experience and their individual responses to violence.

Personal and social resources used to cope with trauma are not only influenced by gender, but also, by the ways in which gender intersects with multiple social identities, such as race and class.

Intersectionality is a useful framework through which to examine how forms of privilege and disadvantage shape women’s experiences of trauma and access to resources.

It acknowledges the social factors that contribute to gender-based violence and subsequent health. An intersectional lens can also improve the way services are organized and provided with attention to multiple forms of oppression and structural violence.

Trauma informed by Intersectionality:

- Oppression exists in various forms (e.g. sexism, racism) and across many levels (e.g. institutions, policies)

- Different forms of oppression interact and shape an individual’s sense of power, resilience, and well-being

- Advantages and disadvantages in the distribution of social resources (e.g. income) affect individuals’ mental health and well-being

- The effects of trauma accumulate over time and interact with other life experiences, impacting health.

“The constellation of women’s lived experiences matters most to their well-being”

IDEAS FOR BRINGING INTERSECTIONALITY INTO PRACTICE

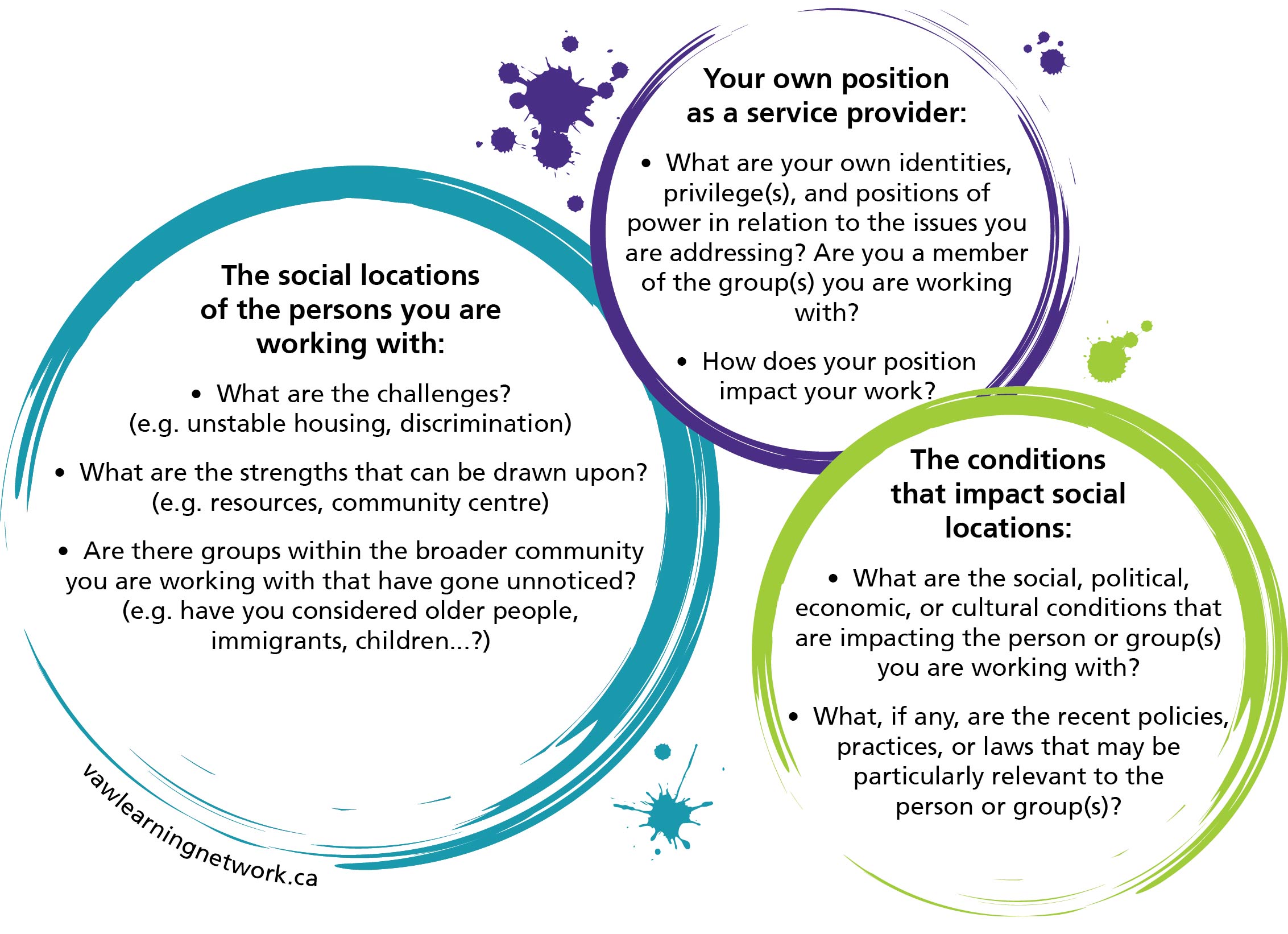

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER WHEN WORKING INTERSECTIONALLY

ACKNOWLEDGING THE INTERSECTIONAL IDENTITIES OF MEN

Intersectionality is a key framework for understanding gender-based violence (GBV) and yet is primarily applied to women survivors in the existing literature.

GBV prevention efforts are increasingly involving boys and men, who are most often the perpetrators of violence against women.

Men’s perpetration of – and attitudes toward – violence is shaped by gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other factors.

There are multiple masculinities, meaning “being a man” or “doing masculinity” varies among different groups of men. Men’s perpetration of violence is therefore best understood in the context of their intersecting identities.

If we want to end gender-based violence, we must work with ALL men. We must meet men where they are and create positive change with educational campaigns and intervention programs reflective of men’s social locations.

At the same time, we must also recognize that men can be survivors of physical and sexual violence, and that their vulnerabilities to and experiences of violence are affected by diverse and challenging intersections of identity.

Programs and services for male survivors of violence must take into account the unique needs of different groups of men to increase the effectiveness of supportive efforts.

MAKING ALL CHILDREN VISIBLE

So, what about children?

Like women and men, children’s experiences of and responses to violence vary along the lines of race/ethnicity, ability, gender, and other social dimensions. Attention to children’s intersectionality provides increased visibility to diversity among children, facilitating a more in-depth understanding of their experiences and the creation of more effective prevention and response efforts.

APPLYING INTERSECTIONALITY: GENERAL STRATEGIES FOR RESEARCHERS

Intersectionality should be integrated in all stages of the research process: theoretical framework, research questions, data analysis, reporting of results, and discussion/conclusion.

The following is a list of general strategies to facilitate this integration:

- Commit to using an intersectional approach.

- Provide a definition of intersectionality that will frame the study.

- Clearly identify which categories of oppression will be studied, the aim of understanding the intersection of these categories, and why these particular intersections were selected.

- Where possible, involve the individuals being studied in shaping the research question and/or determining the issues in need of research in their communities.

- Engage in interdisciplinary collaboration.

- Avoid asking questions that treat identity categories as separate from each other.

- Use samples large enough to allow for the interaction of multiple identities.

- Allow the use art, music or other nonacademic options for participants to share their experiences, narratives or thoughts.

- Supplement quantitative analysis with qualitative analysis and vice versa.

- Consider forms of oppression in relation to power or inequality rather than simply as descriptive characteristics.

- Contextualize findings in relation to broader meso and/or macro level trends.

- Do not assume findings are universally applicable.

- Avoid large group categorizations that risk conflating intragroup differences.

- Recognize how your own values, experiences, knowledge, and social positions influence your approach to research.

INTERSECTIONALITY & HIGHER EDUCATION

Incorporating intersectionality into social justice education programs can enhance students’ understanding of gender-based violence and challenge them to become “catalysts for change”.

Consider setting program goals that encourage students to:

- Develop an awareness of their intersecting identities.

- Become aware of perspectives that differ from their own.

- Identify and analyze systems of oppression.

- Develop the capacity and strategies to alter systems of oppression.

As an educator, it is also important to recognize the role of intersectionality in classroom interactions. Both students and instructors occupy particular social locations that bring complexity to the classroom. Being aware of the lived realities brought by each individual into the classroom and taking these realities into consideration in curriculum planning and in every day interactions with students can enhance educational experiences and challenge oppression.

For educational tools on intersectionality, see the resources page at the end of this newsletter.

RESOURCES

General

For Researchers

For Educators

Everyone Belongs: a toolkit for applying intersectionality

Intersectionality & Higher Education: theory, research, & praxis

Training for Change: practical tools for intersectional workshops

For Service Providers

Domestic Violence: intersectionality and culturally competent practice

Incorporating intersectionality in social work practice, research, policy, and education

For Policy Makers

Intersectionality: moving women’s health research and policy forward

UPCOMING LEARNING NETWORK WEBINAR

Preventing Domestic Homicides: Lessons Learned from Tragedies

December 10, 2015 | 10:00am - 11:00am EST

Dr. Peter Jaffe, Academic Director, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

Domestic homicides are the most predictable and preventable form of homicide. This webinar will present lessons learned from domestic violence death reviews that point to a pattern of risk factors associated with these tragedies as well as consistent recommendations in regards to intervention and prevention.

THE LN TEAM GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES INPUT FROM:

Nicole Pietsch, Coordinator, Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres

WRITTEN BY THE LEARNING NETWORK TEAM:

Linda Baker, Learning Director

Nicole Etherington, Research Associate

Elsa Barreto, Graphic Design

PLEASE EVALUATE US!

Let us know what you think. Your input is important to us. Please complete this brief survey on your thoughts of this newsletter: https://uwo.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3qp8ixEOK0y2fOd

CONTACT US!

www.twitter.com/learntoendabuse

www.facebook.com/TheLearningNetwork

Contact vawln@uwo.ca to join our email list!

All our resources are open-access and can be shared (e.g., linked, downloaded and sent) or cited with credit. If you would like to adapt and/or edit, translate, or embed/upload our content on your website/training materials (e.g., Webinar video), please email us at gbvln@uwo.ca so that we can work together to do so.