Our Work

.

Revisiting Vicarious Trauma in Gender-Based Violence Work: Opportunities for Fostering Vicarious Resilience and Collective Wellbeing

Click here to access the PDF

This Issue-based Newsletter examines vicarious trauma, vicarious resilience, and the need to advocate for structural changes in the gender-based violence sector. It will:

• Present systemic, organizational, and individual factors that influence vicarious trauma

• Highlight the role of organizations in mitigating risks for vicarious trauma

• Offer strategies for what organizations can do to promote the wellbeing of anti-violence workers

Anti-violence workers who provide essential supports, services, and advocacy to survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) are often exposed to trauma in their everyday work. This can result in a number of negative impacts and reactions, which have long been investigated through multiple concepts such as vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue, and burnout.

Preventing vicarious trauma and promoting the wellbeing of anti-violence workers continues to be a key priority for GBV organizations. While current efforts remain critical, they alone may be insufficient to address vicarious trauma. There must also be a focus on fostering vicarious resilience and collective wellbeing within anti-violence workers.

Vicarious resilience describes the positive impacts and personal growth that anti-violence workers experience as they observe the healing, recovery, and resilience of individuals who have experienced trauma. [1]

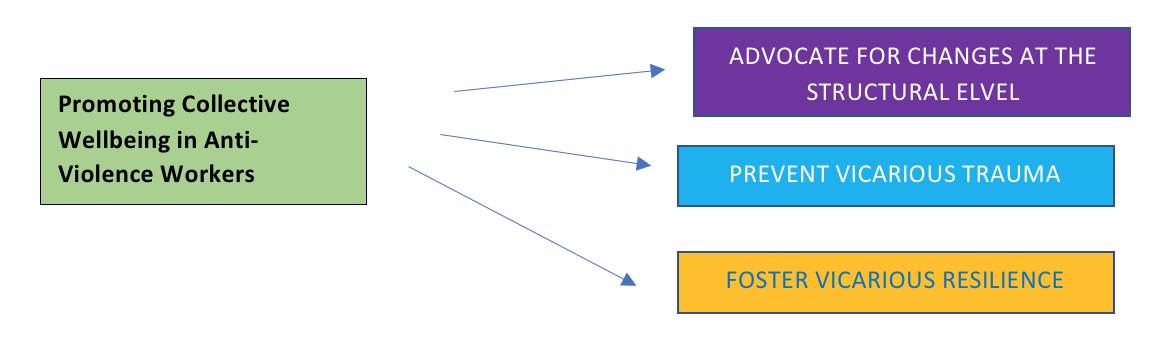

It can be used to promote worker wellbeing in and off itself, with the additional benefit of providing a potential buffer or protector against vicarious trauma. Thus, vicarious resilience offers important considerations for organizations to move from a traditional one-pronged approach that focuses solely on preventing vicarious trauma, to a three-pronged approach that seeks to: (1) advocate for changes at the structural level (i.e. ending the systemic oppressions that influence risk of vicarious trauma and opportunities to build vicarious resilience), (2) prevent vicarious trauma, and (3) foster vicarious resilience among anti-violence workers.

UNDERSTANDING VICARIOUS TRAUMA AND VICARIOUS RESILIENCE

VICARIOUS TRAUMA:

Vicarious trauma describes the negative effects on an individual following exposure to the traumatic experiences of survivors. These effects may mimic the symptoms of someone who has experienced direct trauma. [2]

Hearing stories of the trauma can change the way anti-violence workers see the world around them and can impact their ability to maintain connections with themselves and others.[3]

For instance, an anti-violence worker who is repeatedly hearing stories of intimate partner violence (IPV), may start to believe that all relationships are inherently dangerous or violent. This is because their fundamental beliefs about the world and their sense of safety have changed.

NEGATIVE IMPACTS[4]

• Loss of a sense of meaning in life and/or feeling hopeless about the future

• Difficulty managing emotions

• Relationship and connection problems (e.g. withdrawing from friends and family, avoiding intimacy)

VICARIOUS RESILIENCE:

Vicarious resilience describes a positive transformation where witnessing another individual’s strength and resilience encourages resilience and strength in workers themselves.[5]

Seeing survivors heal and feel empowered can inspire, create hope, and serve as a coping model for anti-violence workers. Anti-violence workers may feel like they can better handle their own struggles and adversities using the lessons learned from individuals they support.

POSITIVE IMPACTS[6]

• Feeling hopeful and able to look at things from a positive point of view

• Reframing their own problems and seeing potential ways forward

• Increased motivation and purpose in life

• Learning how to better deal with their own frustrations

• Feeling inspired by seeing other individuals in their healing journeys

An anti-violence worker may experience vicarious trauma and vicarious resilience separately or at the same time.[7]

FACTORS INFLUENCING VICARIOUS TRAUMA

Not all anti-violence workers will experience vicarious trauma, however there are factors at the systemic, organizational, and individual levels that may increase its likelihood. We explore several of these factors below.

Anti-violence workers’ experiences of vicarious trauma are influenced by historical and ongoing systems of oppression (e.g. colonialism, racism, ableism). These oppressive systems shape the ways that individuals experience violence and trauma, interpret violent and traumatic experiences, and seek help. In bearing witness to a survivor’s trauma, an anti-violence worker may be confronted with the same systems of oppression that affect them and feel a sense of hopelessness or powerlessness in response. As such, anti-violence workers may be coping with the personal trauma of their own oppression and the vicarious trauma from their work. [8]

Further, experiences of vicarious trauma may be impacted by systems of power, including the criminal justice system, child protection system, legal system, healthcare system, and many others that perpetuate systemic violence against individuals based on their identities. For instance, an anti-violence worker who previously had harmful experiences with the healthcare system due to cisnormativity may not feel safe reaching out to that sector. This reduces their ability to seek supports for vicarious trauma.

In response, many marginalized anti-violence workers actively seek to dismantle oppressive systems. Indigenous, Black, and further racialized front-line workers are at the forefront of work on decolonization and anti-racism in the organizations, inter-agency collaborations, and systems in which they work. Such work is valuable and essential. It can also take an emotional toll that needs to be recognized as it increases workers’ vulnerability to stress and vicarious trauma.

Our understanding and prevention efforts are strengthened when we consider and address the role of systemic oppression and a worker’s broader social context in shaping experiences of trauma and vicarious trauma.

ORGANIZATIONAL

The role of organizations cannot be understated and is essential to the well-being of anti-violence workers. Organizational risk factors for vicarious trauma include workplaces with higher cases per worker, greater number of direct work hours with survivors, witnessing or experiencing microaggressions, and working with children who have experienced abuse.[9] Insufficient opportunities for debriefing, peer consultation, and supervision due to staffing shortages and funding can also make anti-violence workers feel like there is no safe space for them to debrief or seek assistance.[10]

Mitigating such risks for vicarious trauma requires meaningful and sustainable changes at all levels within organizations and funding structures to ensure staff and management feel safe and confident in their capacities to help survivors of GBV.

Related Resource: Check out The Mitigating Vicarious Trauma Project led by Ending Violence Association of BC for a wide range of resources on mitigating vicarious trauma for individuals and organizations.

INDIVIDUAL

Personal circumstances and experiences may impact if and how an individual experiences vicarious trauma.

For instance, an individual’s age and experience with systems related to gender-based violence can impact their likelihood of facing vicarious trauma. Younger workers with less experience may face negative outcomes as a result of working with trauma victims and hearing stories of trauma that they have not heard before.[11] They may also find navigating multiple systems (e.g. criminal justice system, child welfare) for the first time daunting and their views of justice and healing may be challenged.[12] In comparison, workers with more experience and years in the field may face cumulative exposure to witnessing trauma.[13]

The role of grassroots movements and lived experience is critical to the work of the GBV sector. Many workers are advocates, activists, and survivors themselves. “Survivor-advocates” (those with their own personal trauma history) are uniquely situated to do this work and support survivors. At the same time, growing evidence suggests that many “survivor-advocates” may be more susceptible to the emotional aspects of the work they do and that they may be at higher risk for vicarious trauma than those without those experiences.[14]

PROMOTING COLLECTIVE WELLBEING IN ANTI-VIOLENCE WORKERS

This section will consider a three-pronged approach to promoting collective wellbeing in anti-violence workers by offering ways to advocate for structural changes, prevent vicarious trauma, and foster vicarious resilience.

ADVOCATE FOR CHANGES AT A STRUCTURAL LEVEL

Vicarious trauma is often conceptualized as an individual struggle rather than being interconnected with further collective struggles and oppressions. Social, political, and economic contexts shape anti-violence workers’ experiences in ways that can contribute to stress and trauma.[15] Addressing vicarious trauma among anti-violence workers requires “structural, cultural, and relational shifts towards collective care within organizations.”[16] Such collective care can extend beyond workers and into the communities served by the organization. As anti-violence workers may be resisting the very same systems of oppression they are advocating against on behalf of the survivors they support, organizations must be attuned to this reality. Likewise, vicarious resilience can be experienced when engaging with collective movements which highlight and build group strengths. By getting involved with and supporting advocacy to end oppression, individuals can foster connections to heal and grow together.

For example:

- Encourage staff to participate in acts of resistance and examine intersections of oppression and violence within and outside of the organization. This may come in the form of group meetings focused on acknowledging and resisting oppression, attending protests and community events, creating and sharing awareness campaigns, and writing letters. Staff who are attuned to their own social location in context of marginalization or privilege can impact their ability to appreciate the positive changes, healing, and recovery shown by survivors and see how they can learn from them.[17]

- Be aware that raising awareness and potentially conducting training on oppression (e.g. anti-racism, challenging heteronormativity) can be difficult and hurtful for anti-violence workers who are members of oppressed groups. They may face discriminatory comments and views from within their organization (e.g. colleague, supervisor) and program partners. Such staff may benefit from frequent check-ins regarding their current caseloads and assignments, and opportunities to connect with others who have shared identities and experiences.[1]

- Advocate for the revamping of funding structures to support the health and wellbeing of anti-violence workers and support longer-term structural change.[18] This involves changing funding structures place the responsibility on individuals to address systemic issues within communities as though they are localized issues unique to that community.[19] It also means advocating for funding for community organizations that is not primarily short-term and project based and does not contribute to the “conditions of stress and burnout, and precariousness in frontline community work.”[20]

- Provide space and support for organizations and allied partners to explore and deconstruct power, privilege, and oppression, and build collective action.[21] It is important for racialized and marginalized individuals to have solidarity from their organization and colleagues so as to not be left on their own to deconstruct oppression. [22]

WHAT GBV ORGANIZATIONS CAN DO TO PREVENT RISKS FOR VICARIOUS TRAUMA

Much of the work on vicarious trauma has focused on individual self-care strategies for anti-violence workers, though this has recently shifted to focus more on the role of the organization and other external factors as a source of protection for those working with survivors of violence. Organizations in the GBV sector play a key role in creating workplace cultures and environments that foster individual and collective wellbeing, and resilience and resistance among anti-violence workers. Below we offer two key strategies for consideration that organizations can do to buffer the risks for vicarious trauma and support staff wellbeing.

WHAT GBV ORGANIZATIONS CAN DO TO MITIGATE RISKS FOR VICARIOUS TRAUMA

Much of the work on vicarious trauma has focused on individual self-care strategies for anti-violence workers, though this has recently shifted to focus more on the role of the organization and other external factors as a source of protection for those working with survivors of violence. Organizations in the GBV sector play a key role in creating workplace cultures and environments that foster individual and collective wellbeing, and resilience and resistance among anti-violence workers. Below we offer two key strategies for consideration that organizations can do to buffer the risks for vicarious trauma and support staff wellbeing.

1. BECOME A TRAUMA- AND VIOLENCE-INFORMED ORGANIZATION

Trauma-and violence- informed organizations (TVI) inherently work to understand and mitigate risk factors that are associated with vicarious trauma. They ensure that the personal and vicarious trauma of anti-violence workers, who may or may not be survivors, is recognized. They also encourage anti-violence workers who may be survivors themselves to direct their unique strengths towards the work they do with the survivors they serve, such as sharing their own survivor story.[23] Naming and acknowledging survivorship may make anti-violence workers feel validated and increase their well-being.[24]

TVI organizations are also attuned to how trauma interrelates with multiple systems of oppression, historical contexts, and intersecting identities including gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. This means that organizations are committed to and intentional about implementing active measures to address bias, microaggressions, discrimination, and oppression, and incorporate policies and practices that acknowledge and mitigate effects of historical trauma.[25]

2. PROVIDE OPPORTUNITIES FOR QUALITY MENTORING AND SUPERVISION

Organizational leaders are uniquely positioned to offer opportunities for quality mentoring and supervision to their staff. This includes recognizing the risks of adverse impacts inherent in anti-violence work, validating the challenging and valuable nature of this work, and providing targeted skills-building training (e.g. setting boundaries, recognizing potential impacts of trauma on workers).[26]

Regular check-ins with staff, particularly following stressful situations, can allow staff and supervisors to review the challenges and successes, and consider alternative responses in the event of another similar situation. Peer group debriefs may also be useful as anti-violence workers can share similar concerns and challenges which can help validate their feelings and the challenging nature of the work. When there is respectful and authentic communication between anti-violence workers and supervisors, anti-violence workers may be more likely to voice their needs and identify areas of concern (e.g. high caseloads, requests for time off, need of certain resources).

Related Resource: A Guide to Trauma-Informed Supervision

WHAT GBV ORGANIZATIONS CAN DO TO FOSTER VICARIOUS RESILIENCE

Anti-violence workers have long described the positive impacts and changes that they experience through their work. For instance, they’ve called their work “rewarding” and “inspiring” and have found that working with those who have experienced trauma can strengthen skills to cope with stress and/or trauma in their own personal lives and help them become more resilient.[27]

An increased understanding of such impacts could help organizational leaders build on the existing strengths and resources of their staff and identify strategies to encourage growth with a focus on supporting vicarious resilience, rather than focusing solely on preventing vicarious trauma.[28]

NEW PROJECT: Algonquin College - Victim Services Providers and Vicarious Resilience

This project is focused on vicarious resilience in victim service workers. A toolkit will be developed on how to build resilience and create more training.

“If we ignore the pain of vicarious trauma and the power of vicarious resilience, the cycle and chaos of trauma can become embedded in the culture of our organizations and movements.”[29]

Note: A focus on fostering vicarious resilience is not meant to ignore the realities of vicarious trauma and the demanding and emotional conditions of GBV work. Rather, vicarious resilience is meant to be used as a positive resource that can be sought and nurtured to mitigate exhaustion and other negative effects experienced by anti-violence workers.

What GBV Organizations Can Do To Foster Vicarious Resilience

• Acknowledge acts of resistance demonstrated by survivors that may not fit “traditional” models of resiliencebut work to dismantle harmful and violent systems and structures faced on a daily basis.

• Ensure that vicarious resilience is included in high-quality training and education on vicarious trauma for all

levels of staff (e.g. frontline workers, management, Board).

• Build a group that regularly meets to learn from the resilience of survivors through reading personal memoirs,

watching videos, and inviting survivors to speak.

• Incorporate an action plan for vicarious resilience in organizational strategic plans.

• Develop a peer mentor program amongst staff with a focus on discussions about fostering hope, finding

meaning in the work, and regular de-briefing.

• Highlight and share stories of survivor resilience and its impacts on team members (with permission) in staff

meetings.

• Offer opportunities for "check-ins" for both vicarious trauma and resilience in individual or group meetings

while allowing staff to reach out and seek support on their own terms.

• Create opportunities for staff to acknowledge and learn from survivor’s interests and skills (e.g. such as a

paint or poetry night).

• Highlight various ways staff members continue to resist social injustices and engage in collective advocacy.

DEAR SISTER

Dear Sister,

May your beautiful heart-space remain

As open as the sky is wide

And blue And far

And as receiving as the waters that flow run deep.

Dear Sister,

May your heart with every beat give permission

To continue its healing

And to keep you Calm and Strong and Kind

As only

You

can

be.

Dear Sister,

May the love and peace of this Universe

Show Herself to you

With bright and sparkling eyes,

Arms held open, all the miles wide.

And My Dearest Sweetest Sister,

May the love you lift up for Yourself

Housed in the deepest chamber of your heart,

Sometimes broken and bruised,

Sometimes bursting with

Grace

And Pain

And Gratitude

Remain the steadfast beacon

That with Patience and Remembering,

Will forever be your guide

And hold you Safe and Warm and Seen,

For exactly

Who

YOU

are.

Ryane Miller, MSW, LCSW, VSP Lead Advocate- CARE Violence Prevention & Response Office Adjunct Professor- School of Social Work University of North Carolina Wilmington

Ryane started writing poetry as an outlet and self-care tool to assist her in processing the grief and trauma witnessed in her work as a trauma counselor and university survivor advocate. Over the last few years this gift of creative expression has grown from a way to work through vicarious trauma, into a vehicle to honor survivors’ truths and experiences, and to foster vicarious resilience. Ryane’s writing allows her to stay grounded in focusing on her clients’ growth and strengths, so she can continue to do this incredibly important work.

The featured poem, “Dear Sister” was inspired by the growth and resilience factors Ryane has witnessed in her work with trauma clients. Often, feelings of guilt, shame and self-blame are identified and explored by survivors who are ready to do so. In some cases, clients work toward re-building a loving relationship with themselves. This act of courage and resilience can result in a ripple-effect of positive change and growth for the survivor, as well as the experience of vicarious resilience for the loved ones and support systems surrounding them. This poem is humbly dedicated to the whole of the survivor community.

CONCLUSION

The collective wellbeing of anti-violence workers is critical to the important and challenging work of ending gender-based violence. Vicarious trauma prevention is only one piece of the puzzle; fostering vicarious resilience and advocating for changes at the structural level are also necessary to promote the well-being of anti-violence workers.

We invite you to share further ways you have found to support collective wellbeing and vicarious resilience with us on social media or by email!

https://www.facebook.com/LNandKH

Please Evaluate this Issue

Let us know what you think. Your input is important to us. Please complete this brief survey on your thoughts of this Issue.

The Learning Network

Linda Baker, Learning Director, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

Dianne Lalonde, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

Jassamine Tabibi, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

Graphic Design

Emily Kumpf, Digital Communications Assistant, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children

Suggested Citation

Tabibi, J., Baker, L., & Lalonde, D. (2021). Revisiting Vicarious Trauma in Gender-Based Violence Work: Opportunities for Fostering Vicarious Resilience & Collective Wellbeing. Learning Network Issue 36. London, Ontario: Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children. ISBN# 978-1-988412-54-2

Contact Us!

https://www.facebook.com/LNandKH

Click here to sign up for our email list and receive resources and information about coming events.

[i] Hernandez, P., Gangsei, D., & Engstrom, D. (2007). Vicarious resilience: A new concept in work with those who survive trauma. Family Process, 46(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00206.x

[2] Pai, A., Suris, A.M., & North, C.S. (2017). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behavioural Sciences, 7(1), 7. doi: 10.3390/bs7010007

[3]McCann, I, & Pearlman, L. (1990). Vicarious Traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131-149. Available at https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/BF00975140.pdf ; McCann, I, Sakheim, D, & Abrahamson, D. (1988). Trauma and Victimization: A Model of Psychological Adaptation. The Counseling Psychologist, 16(4), 531-594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000088164002; McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Constructivist self-development theory as a framework for assessing and treating victims of family violence. In S. M. Stith, M. B. Williams, & K. H. Rosen (Eds.), Violence hits home: Comprehensive treatment approaches to domestic violence (pp. 305–329). Springer Publishing Co.; Pearlman, L, & Caringi, J. (2009). Living and Working Self-Reflectively to Address Vicarious Trauma. In C. A. Courtois & J. D. Ford (Eds.), Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders. New York: The Guilford Press.; Pearlman, L, & MacIan, P. (1995). Vicarious Traumatization: An empirical study on the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 26(6), 558-565. Available at https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/1996-15656-001 ; Pearlman, L, & Saakvitne, K. (1995). Trauma and the therapist: countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. New York: W.W. Norton.

[4] Office for Victims of Crime. What is Vicarious Trauma? U.S. Department of Justice. Available at https://ovc.ojp.gov/program/vtt/what-is-vicarious-trauma

[5]Hernandez, P., Gangsei, D., & Engstrom, D. (2007). Vicarious resilience: A new concept in work with those who survive trauma. Family Process, 46(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00206.x

[6]Engstrom, D., Hernandez, P., & Gangsei, D. (2008). Vicarious resilience: A Qualitative Investigation Into Its Description. Traumatology, 14(3), 13-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608319323 ;Hernandez, P., Gangsei, D., & Engstrom, D. (2007). Vicarious resilience: A new concept in work with those who survive trauma. Family Process, 46(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00206.x

[7]Arnold, D., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R., & Cann, A. (2005). Vicarious posttraumatic growth in psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45, 239 –263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022167805274729 ; Hernández-Wolfe, P., Killian, K., Engstrom, D., & Gangsei, D. (2015). Vicarious resilience, vicarious trauma, and awareness of equity in trauma work. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 55, 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167814534322

[8] Powell, S. (2021). Vicarious Trauma, Vicarious Resilience, & Systemic Oppression: The Responsibility of Organizations & Movements to Trauma Workers. Medium. Available at https://shobanapowell.medium.com/vicarious-trauma-vicarious-resilience-systemic-oppression-the-responsibility-of-organizations-ab6e0102cee1

[9] Benuto, L. T., Singer, J., Gonzalez, F., Newlands, R., & Hooft, S. (2019). Supporting those who provide support: Work-related resources and secondary traumatic stress among victim advocates. Safety and Health at Work, 10(3), 336–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2019.04.001; Dworkin, E. R., Sorell, N. R., & Allen, N. E. (2014). Individual-and setting-level correlates of secondary traumatic stress in rape crisis center staff. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(4) 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514556111; Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14(2), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608319083; Klinic Community Health Centre. (2013). Trauma-informed: The trauma toolkit; McKim, L. L., & Smith-Adcock, S. (2014). Trauma counsellors’ quality of life. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-013-9190-z; Wood, L., Wachter, K., Wang, A., Kammer-Kerwick, M., & Busch-Armendariz, N. (2017). Technical Report – VOICE: Victim services occupation, information, and compensation experiences survey. https://sites.utexas.edu/idvsa/research/domestic-violence-interpersonal-violence/victim-services-occupation-information-and-compensation-experiences-survey-2017/; (2017). Vicarious Trauma and Resilience. Ending Violence Association of B.C.

[10] Babin, E. A., Palazzolo, K. E., & Rivera, K. D. (2012). Communication skills, social support, and burnout among advocates in a domestic violence agency. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(2), 147–166. Killian, K. (2008). Helping Till It Hurts? A Multimethod Study of Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Self-Care in Clinicians Working With Trauma Survivors. Traumatology. 14(2), 32-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608319083

[11] Dworkin, E. R., Sorell, N. R., & Allen, N. E. (2014). Individual-and setting-level correlates of secondary traumatic stress in rape crisis center staff. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(4) 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514556111 ; Klinic Community Health Centre. (2013). Trauma-informed: The trauma toolkit; Wood, L., Wachter, K., Wang, A., Kammer-Kerwick, M., & Busch-Armendariz, N. (2017). Technical Report – VOICE: Victim services occupation, information, and compensation experiences survey. https://sites.utexas.edu/idvsa/research/domestic-violence-interpersonal-violence/victim-services-occupation-information-and-compensation-experiences-survey-2017/.

[12] Ending Violence Association of BC. (2021). Vicarious Trauma Tip Sheet for Community-Based Victim Service Workers. Available at https://endingviolence.org/publications/new-resources-mitigating-vicarious-trauma/

[13] Cummings, C., Singer, J., Hisaka, R., & Benuto, L. T. (2018). Compassion satisfaction to combat work-related burnout, vicarious trauma, and secondary traumatic stress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-16.https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518799502; Klinic Community Health Centre. (2013). Trauma-informed: The trauma toolkit. Trauma counsellors’ quality of life. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-013-9190-z

[14] Frey, L. L., Beesley, D., Abbott, D., & Kendrick, E. (2017). Vicarious resilience in sexual assault and domestic violence advocates. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000159 ; Hensel, J. M., Ruiz, C., Finney, C., & Dewa, C. S. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21998 https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000159; Kulkarni, S., Bell, H., Hartman, J. L., & Herman-Smith, R. L. (2013). Exploring individual and organizational factors contributing to compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout in domestic violence service providers. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 4(2), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.5243/jsswr.2013.8; Slattery, S. M., & Goodman, L. A. (2009). Secondary traumatic stress among domestic violence advocates: Workplace risk and protective factors. Violence Against Women, 15(11), 1358–1379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801209347469

[15] Skinner, A. (2013). Unsettling the Currency of Caring: Promoting Health and Wellness at the Frontlines of Welfare State Withdrawal in Toronto. [Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto]. Available at https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42937/1/Skinner_Ana_J_201311_MA_Thesis.pdf

[16] Halper, A. (2021). Moving Beyond Self-Care to Address the Roots of Vicarious Trauma. Relias. Available at https://www.relias.com/blog/moving-beyond-self-care-roots-of-vicarious-trauma

[17] Hernandez-Wolfe, P., Killian, K.D., Engstrom, D., & Gangsei, D. (2014). Vicarious Resilience, Vicarious Trauma, and Awareness of Equity in Trauma Work. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 55(2), 153-172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167814534322

[18] Skinner, A. (2013). Unsettling the Currency of Caring: Promoting Health and Wellness at the Frontlines of Welfare State Withdrawal in Toronto. [Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto]. Available at https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42937/1/Skinner_Ana_J_201311_MA_Thesis.pdf

[19] Skinner, A. (2013). Unsettling the Currency of Caring: Promoting Health and Wellness at the Frontlines of Welfare State Withdrawal in Toronto. [Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto]. Available at https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42937/1/Skinner_Ana_J_201311_MA_Thesis.pdf

[20] Skinner, A. (2013). Unsettling the Currency of Caring: Promoting Health and Wellness at the Frontlines of Welfare State Withdrawal in Toronto. [Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto]. pg 13. Available at https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42937/1/Skinner_Ana_J_201311_MA_Thesis.pdf

[21] Skinner, A. (2013). Unsettling the Currency of Caring: Promoting Health and Wellness at the Frontlines of Welfare State Withdrawal in Toronto. [Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto]. Available at https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42937/1/Skinner_Ana_J_201311_MA_Thesis.pdf

[22] Skinner, A. (2013). Unsettling the Currency of Caring: Promoting Health and Wellness at the Frontlines of Welfare State Withdrawal in Toronto. [Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto]. Available at https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/42937/1/Skinner_Ana_J_201311_MA_Thesis.pdf

[23] Wilson, J.W., & Goodman, L.A. (2021). “A Community of Survivors”: A Grounded Theory of Organizational Support for Survivor-Advocates in Domestic Violence Agencies. Violence Against Women, pg3. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220981143

[24] Wilson, J.W., & Goodman, L.A. (2021). “A Community of Survivors”: A Grounded Theory of Organizational Support for Survivor-Advocates in Domestic Violence Agencies. Violence Against Women, pg3. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220981143

[25] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Available at https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

[26] Brend, D. M., Krane, J., & Saunders, S. (2020). Exposure to trauma in intimate partner violence human service work: A scoping review. Traumatology, 26(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000199

[27] (2017). Vicarious Trauma and Resilience. Ending Violence Association of B.C.

[28] Frey, L. L., Beesley, D., Abbott, D., & Kendrick, E. (2017). Vicarious resilience in sexual assault and domestic violence advocates. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000159

[29] Powell, S. (2021). Vicarious Trauma, Vicarious Resilience, & Systemic Oppression: The Responsibility of Organizations & Movements to Trauma Workers. Medium. Available at https://shobanapowell.medium.com/vicarious-trauma-vicarious-resilience-systemic-oppression-the-responsibility-of-organizations-ab6e0102cee1

All our resources are open-access and can be shared (e.g., linked, downloaded and sent) or cited with credit. If you would like to adapt and/or edit, translate, or embed/upload our content on your website/training materials (e.g., Webinar video), please email us at gbvln@uwo.ca so that we can work together to do so.